When McLean Stevenson Left M*A*S*H, Audiences Were Truly Heartbroken

When the television show “M*A*S*H” was put in a position where it needed to write off one of its most beloved actors and characters, its writers made a remarkably bold decision. They would kill him off, a fairly unconventional twist for a sitcom with all-ages appeal. The resulting impact would become one of the show’s most significant legacies and something that proved its “War Is Hell” bonafides. It was a controversial and risky move, but for a show set during the Korean War that was, for all intents and purposes, about the Vietnam War, it was a necessary one.

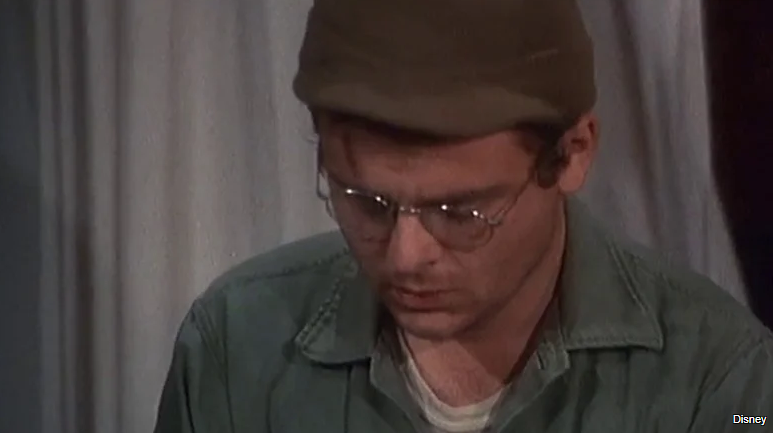

Still, Henry Blake (McLean Stevenson) was essential to that special “M*A*S*H” feeling, that mix of dysfunction and sentimentality that led to the show lasting as long as it did. The show could have simply written him off between seasons like it did around the same time for “Trapper” John McIntyre (Wayne Rogers), and left a positive note on his departure (as well as the door open for potential reappearances, as sitcoms do).

Instead, he died offscreen, in shocking fashion after an effective episode-long tribute, the season 3 finale “Abyssinia, Henry.” When informed that he has been given the opportunity to return home, he makes plans to do so. He gives the unit a bittersweet farewell, complete with a drunken party at local bar Rosie’s. His final boarding on a helicopter away from the camp is incredibly sad, but with a warm feeling: he might be leaving the cast, but he will at least return home to his wife and kid.

And then, in the episode’s final scene, with the show’s surgeons in the middle of intense operating work, we learn Henry’s plane was shot down over the Sea of Japan. “There were no survivors.”

Suicide is painless

“M*A*S*H” was unique among ’70s sitcoms. Not quite as cynical as the book series by “Richard Hooker” (actually military surgeon H. Richard Hornberger and W.C. Heinz) as well as the 1970 film directed by Robert Altman, it still gave audiences an acerbic portrait of military dysfunction. Telling the story of the 4077th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital during the Korean War, the show was a forerunner for something like the 2000s sitcom “Scrubs” in its mix of humor and medical drama pathos, although not as weird.

Compared to most other sitcoms, it was edgy, complete with hardcore drinking and objectification (or worse) of the camp’s nurses. Even the laugh track was, according to co-creator Larry Gelbart, “a thorn in our side.” While the show had a great ensemble, Hawkeye Pierce (Alan Alda) was the clear lead (which became especially galling for co-star Wayne Rogers, per Outsider), the relaxed and cool conscience of the camp whose every joke has Marx Brothers wit. His drinking and womanizing, a defense mechanism for the psychological toll of the war, let the series walk the line of comedy and drama.

Henry was commanding officer of the 4077th. If his leadership style veered on the unprofessional side, that was why viewers loved him. It was all the better that he often butted heads with the show’s early-season antagonists, Frank (Larry Linville) and Margaret “Hot Lips” Houlihan (Loretta Swit). He was wise too. When he had to comfort Hawkeye after the death of his friend in the first season’s legendary “Sometime You Hear The Bullet,” he was frank. “Rule number one is ‘young men die.’ And rule number two is ‘doctors can’t change rule number one.'”

Stevenson got discharged

Because of how indispensable McLean Stevenson’s performance as Henry was to the fabric of “M*A*S*H,” the loss of the character would signal a huge shift in the show’s dynamics. But after three seasons on the show, he had made his decision. “M*A*S*H” might have spoken to America’s issues, but it couldn’t keep everybody on the cast satisfied.

Some of Stevenson’s issues with the show were remarkably similar to Wayne Rogers’ issues, particularly the feeling from both men that they were playing second fiddle to Alan Alda’s Hawkeye. If Henry wasn’t especially involved in a plotline, Stevenson had to settle for getting some of the funniest bits of the episode, but with reduced screen time than anybody else in the main cast.

According to writer Mark Evanier, Stevenson “wasn’t happy on ‘M*A*S*H.'” Besides feeling underserved with respect to the spotlight, he also felt the cast and crew weren’t properly cared for by 20th Century Fox, which produced the show. His request for a percentage raise was denied, and he felt it was made clear to him that he wasn’t responsible for the show’s success.

In the midst of his dissatisfaction with the production, he was given the chance to spread his performing wings in a different format: late-night talk shows. As a guest host on “The Tonight Show With Johnny Carson,” he demonstrated a degree of skill and ease, and was, per Evanier, “pretty good at it.” NBC offered him a deal that was much more lucrative than anything “M*A*S*H” could give, and he would be given the spotlight, as well as the possible chance to become permanent host of “The Tonight Show.” He took the deal.

Shot down over the Sea of Japan

McLean Stevenson left “M*A*S*H” for the seemingly greener pastures promised by the NBC deal.

In the meantime, he was written off towards the end of the show’s third season in 1975. Knowing he would depart from the show gave creators Larry Gelbart and Gene Reynolds ample time to give Henry Blake a proper sendoff, but some ideas for the specifics kept coming up among the writers. Reynolds recalled that the question around Henry’s departure was “what if he went into the drink?”

“What the actor wants, and what the writer needs, are two different things,” Reynolds told the Television Academy. The same could go for what the audience wants. “M*A*S*H” was often hilarious and silly, a classic farcical show complete with pranks, cross-dressing, and games gone wrong. That it walked the line between sitcom and drama as deftly as it did was a testament to its writers’ skill, because the emotional moments of the show still ring true, in groundbreaking episodes like “George” as well as many others. Never was it more gut-wrenching than in “Abyssinia, Henry,” the great Henry Blake farewell show.

Henry went into the drink. The friendly small-town doctor who was handed control of a war hospital that was often too chaotic for him was killed offscreen, just after a moment of his greatest triumph. The scene in the operating room where the cast learns of his death was infamous: in one take, panning from Radar (Gary Burghoff) as he tearfully announces the news to the other surgeons, who choke up and cry through their masks, but have to keep working. Per Outsider, the cast hadn’t been informed of the scene beforehand, and their reactions were genuine.

Henry Blake and Vietnam

Everything “M*A*S*H” stood for was tested by the final moments of “Abyssinia, Henry.” At the time, the shock was immense. Even McLean Stevenson, who had practically begged to be written off the show, was so upset on learning the news that he “skipped the wrap party,” according to Outsider.

When the episode finally premiered, Gene Reynolds (per Slate) got a call from one distressed viewer who told him that killing off Henry “was not necessary, it’s just a little comedy show.” According to the documentary “Making M*A*S*H,” the network received over a thousand (mostly angry) letters following the episode, with the constant theme being that this was a sitcom — how could you kill such a beloved character? One-off characters had died in “M*A*S*H” before, but this was Henry.

While “M*A*S*H” was superficially dealing with the Korean War some decade-plus earlier, Vietnam was always on its creators’ minds. As the so-called “first televised war,” it was experienced by many Americans as pure data. Reynolds felt that distance was unhealthy, ultimately saying in “Making M*A*S*H” that “if there is such a thing as the loss of life there should be some connection … People like Henry Blake are lost in war.”

Many movies would go on to reckon with the Vietnam War but because “M*A*S*H” did it in such a cozy, familiar package, it made for one of the most upsetting and groundbreaking moments in the show.

Unfortunately for Stevenson, those same upset viewers failed to follow him to his future endeavors on NBC. Per his obituary, he always felt his mistake was in assuming people loved him when, in truth, “everybody loved Henry Blake.” But there was no character without his big-hearted, hilarious performance.