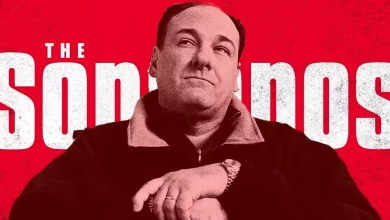

‘The Sopranos’ Is All About Those Damn Ducks

Twenty-five years later, The Sopranos still makes a justifiable case as the best television series ever made. It helped establish HBO as the premier place for TV, the antihero era, and the idea of television as a home for serious filmmaking and writing. But part of what makes The Sopranos great is how capably it maintained so many of the elements of television that it was simultaneously rebelling against: over-serialized storylines, an episodic structure, and aimless drama. The Sopranos has the fun and violence of pulpy TV, but is as dense and rich as a big novel. Plenty of its symbols and allegories and, yes, dreams are still being deciphered.

One of those symbols, appearing in the very first episode of the series, is ducks. Ducks with their ducklings that flap their wings in Tony Soprano’s pool to his big, gleeful delight as he feeds them bread, badgers his family about them, and reads books trying to learn about them. Those ducklings eventually figure out how to fly, and as a family the ducks all fly away together, away from the Soprano residence, which triggers the first panic attack of the show and essentially starts our story off.

Tony is recounting all of this to Dr. Jennifer Melfi, his psychiatrist that he’s not supposed to be talking to as a member of the mafia. Melfi, and the therapy stuff in general, tend to get a bad rap to this day, usually from people who are more interested in the mob scenes, or just think Melfi is a bad therapist. I agree that it takes a while for the show to figure out how Melfi best works as a character, which is as a way for Tony to share his internal monologue and for Melfi to be more directly an audience surrogate, both attracted to and repelled by Tony’s behavior.

If you’ve watched at least the first episode of The Sopranos, you might be wondering what else there is to say about the ducks. Everyone knows what the ducks mean. Tony and Melfi literally say it: He associates the ducks with his family, and seeing them fly away triggered his fears about losing his family, thus his panic attack. Yeah … I guess. But that scene takes on a different context once the story is finished, and it becomes clear that Melfi and Tony’s sessions were always dysfunctional, that her shallow analysis of his behavior only ever placated him at best and enabled him at worst. Nobody wants to lose their family. That’s not deep. The ducks are about the things that Tony won’t say, that he never says, either to Melfi or himself.

A big theme of The Sopranos is Tony’s deeply repressed feelings about his life in the mob. Over the course of the series, you learn a lot about Tony’s upbringing: How his father and his uncle were big-time captains in New Jersey, how he played football while in high school (but never had the makings of a varsity athlete), how he looked up to his uncle Dickie, how he lasted only a semester at Rutgers (but he does understand Freud!), and how he’s still trying to satisfy his mother.

Tony’s first panic attack happens when he’s a kid; he’s just watched his father chop Mr. Satriale’s finger off because of a gambling debt. Later, his father sits him down to explain why he had to do what he did, and also praises him for not running away in fear or shock at what he saw; he’s a little impressed that Tony could handle watching that. Afterward, Tony’s parents are in the kitchen preparing the assorted meat from Satriale’s, which they got for free of course, and Tony watches the delight on his mother’s face as she prepares all of it and flirts with her husband, immediately triggering the first of Tony’s panic attacks. In fact, many of Tony’s panic attacks tend to be related to family—his mother specifically. They also tend to be related to food. When Tony saw those ducks fly away, he was grilling sausages. When Tony talks to Melfi about that panic attack as a kid, she makes the point that there was more than likely a connection between seeing where that meat came from and how his father got it, and the joy and satisfaction it brought to his never-happy mother that might have triggered something that overwhelmed him into passing out.

There’s an incredible scene from Season 5 where Tony talks to Melfi about his concerns about his cousin Tony Blundetto, who has been recently released from prison. Tony wants to take care of his cousin and look out for him because he feels bad that he spent 15 years in prison for a hijacking that Tony was supposed to participate in. As Tony gets into his feelings of guilt, he starts breathing more shallowly and blinking rapidly, until he fully confesses that the real reason he missed the hijacking is because he had a panic attack after fighting with his mom. It’s an electric scene from James Gandolfini as a performer, but it also gets at Tony’s overlying issue. Being in the mob, living a gangster lifestyle, is stressing him to the point of panic. He himself cannot deal with his deep need to escape that life, so it’s manifesting itself in these collapses and attacks. Tony routinely comes to the verge of realizing this about himself through Melfi’s psychoanalysis, but almost always changes course or moves on in order to fight this lightbulb moment. Tony fights this reality partially because he can’t process his life being a lie, but also because he doesn’t actually want to change, he just wants to get better at tamping down those feelings, and that’s what Melfi ultimately helps him do.

And that brings us back to the ducks. Another theme of The Sopranos is Tony’s love of animals. He can casually kill his own friends and family members, but turns into a big kid around animals, wanting only to nurture and protect them. The obvious meaning is that Tony loves animals because of their innocence, and animals are innocent. More importantly, however, they don’t have obligations. They aren’t tied down by responsibility or their past actions. They are free to come and go as they please.

Those ducks represent the yearning at the heart of the series: the desire to be able to escape our self-made prison. The dream of flying away. The Sopranos, above all else, is about our inability to escape—from the mafia, work, family, etc. We use therapy, religion, self-care, drugs, violence, and anything else we can grab onto to try and get around this fact, to pretend for awhile that we can be free and can escape the things we’ve done. The ducks can just fly away, spread their wings and careen off into the unknown, unburdened by the world they just inhabited or a mob boss’s love for them. They get to leave and he doesn’t. He’s in the clutches of his family forever. Cut to black.